based on an article that originally appeared in “Mandolin Magazine,” Fall 1999.

Download the pdf of the sheetmusic associated with this article: Branzoli_duet

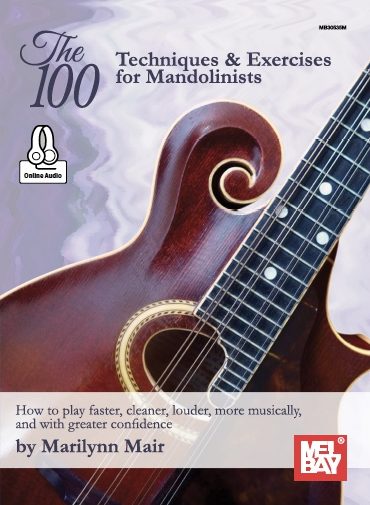

I’m a “classical” mandolinist, and at times I’ve been asked exactly what that designation means. History traces the roots of “classical” back to Ancient Greece, where it was used to describe an artistic style marked by clarity, harmony, order, balance, structure, and symmetry; universal in appeal and humanistic in focus. Throughout history, neo-classical and classical revival styles have always touched back to these principles while moving ahead to broaden the stylistic definition. This concept of “classical,” applied to mandolin performance, resonates well with me. I see “classical mandolin” not as a set of rules or a restriction of materials, but rather, as a clear and universal approach to music, ongoing and evolving through time.

Recently a colleague and I were asked to come up with a universal definition of music and arrived at one that pleased us for its simplicity and breadth: “Music is an expression of thought and feeling, wrapped in culture and history, and transcending both.” The commonalties that unite diverse styles of music allow a serenade by Mozart, a choro by Jacob do Bandolim, and a Bill Monroe performance of “Blue Moon of Kentucky” to share a timeless appeal. Each is a perfect musical expression; and rating one against another is not the point. A definition of “classical mandolin,” to my way of thinking, is part technique, part repertoire, part quality of sound, part interpretation, part venue, and part intent, but mostly it’s a matter of style. In these articles I’ll try to shed some light on various aspects of the complex and incandescent world of classical mandolin, a world I’m pleased to be part of.

One of the most recognizable attributes of good classical mandolin technique is a smooth, expressive tremolo. Like the bowed tone of an accomplished violinist, the tremolo allows for the lengthening of a note and, through judicious application, the creation of an interpretive phrase. Tremolo is not essential for phrasing, and even a great tremolo can’t make up for lack of musical intelligence. But in the hands of an artistic performer the tremolo can be an unparalleled vehicle for communicating emotion through sound. Developing a good tremolo, technically, is a slow and sometimes frustrating process that few can shortcut. But for a classical player it’s an essential tool; and for performers of other styles it’s an enriching addition. Once mastered, a good tremolo will be yours for life, even when your scales and arpeggios grow rusty and your hand coordination less than accurate, whether from age or simply lack of practice. If you are a classical mandolinist, or interested in performing like one, developing a good tremolo is a key ingredient.

The tremolo is actually just a series of down and up strokes, but to develop its expressive qualities you’ve got to start from a good foundation. To begin you need to assess your regular picking style to insure that the ease and flexibility are there to allow for development. A runner who is out of breath after a couple of blocks clearly can’t complete a marathon, and a normal family car just isn’t up to the demands of the Indy 500. Begin your diagnostic check by picking down and up slowly and regularly on your open D or A string. Is your wrist relaxed? Is you forearm relaxed? Is your picking even? As your pick moves the string, does the string also move your pick? Can you continue to pick this way for a couple of minutes without a change in arm tension or sound production? Can you play without anchoring your right-hand pinkie on the face of the mandolin? (Dragging it is OK; anchoring it is not.) If the answers to these questions are “yes,” then you are ready to proceed.

Play the following pattern at a slow even tempo (mm = 50-60.) on your open A string. This is a 4-bar phrase: 4 quarter-notes, downstroke; 8 eighth-notes, downstroke; 16 16th-notes, alternating down & upstrokes; 32 32nd-notes, alternating down & upstrokes. Do not anchor you right hand pinkie on the face of the mandolin. Play in a relaxed but even manner. Use a small heavy pick, and hold it lightly so it pivots between your fingers as it strikes the strings. On your downstroke be sure the pick comes to rest on the adjacent pair of strings before you begin your upstroke. Do not change your hand position at all between the down and up strokes, simply pivot your hand from the wrist (not from the elbow.)

If your picking breaks down in the middle of the 32nd notes, you’ve probably begun at too fast a tempo to be able complete the exercise without losing control. Just start again at a slower pace. As you proceed through the exercise you’ll probably feel your wrist tighten slightly in the last measure, which is normal. Each time you repeat the exercise use the first measure of quarter notes to consciously relax your wrist before you build up the picking speed again. Optimally you should be able to repeat the exercise 10-20 times without stopping, but in no case should you continue to the point of pain. Remember, at this stage in your development you’re only responsible for maintaining relaxation and steady regular picking; speed comes later.

If you’re still having difficulty after working on this for a few days you may need to consider changing your wrist position to allow for greater flexibility. Flexibility is crucial to develop the speed and control needed for a good tremolo, and any unnecessary tension will stand between you and your goal. Check your wrist first for evidence of tension. Does it pivot freely when you pick? Is your “down-up” picking pattern accomplished with a “drop-lift” motion rather than a “push-pull”? (This lessens wrist tension.) If not, try slightly arching your wrist to encourage freer mobility. Remember, relaxation with control is the key.

Assuming you’re progressing, your next step is to transform your “sewing machine” perpetual motion into an expressive vehicle for interpretation. Practice increasing and decreasing your thumb pressure on the pick to change the volume of a note over several beats in a slow crescendo-decrescendo. With that accomplished try changing volume abruptly, or introducing an accent into the middle of a continuous tremolo by quickly increasing and then releasing the pressure of your fingers on the pick. Next, try connecting a passage of notes by means of tremolo. Play passages of varied note lengths to be sure you continue to count during your tremolo, so the technique doesn’t obscure the rhythm. Play passages with and without tremolo to see what a given phrase gains and loses with the introduction of tremolo. Then, try to incorporate tremolo notes and phrases into a single-stroke texture to see how they change the interpretation. In short: experiment.

I’ve included a duet exercise from Guiseppe Branzoli’s mandolin method of 1882 to help you experiment with the effects of your newly-minted expressive tremolo. I’ve marked phrases and dynamics, and given suggestions for fingering. Since classical music is always written music, I haven’t included tablature with the example. This is not to exclude non-readers, but to encourage you to take the first step toward becoming a classical mandolinist by vaulting the note-reading hurdle. Tremolo the notes under each slur without a break and stop your tremolo briefly between phrases. I’ve used 2nd and 3rd positions briefly to keep tremolo phrases on one string, but you can play the entire piece in 1st position if you wish. Note that some of the fingerings (ex.: measure 12) are used to avoid breaking the phrase by using one finger for two consecutive notes. Have fun, and a warm welcome to my world of classical mandolin!